Sudan’s Pro-Democracy Protests

‘‘Sudan Bukra TV will be sharing information on the logistics of Sudan’s resistance movement”, a Sunday night tweet announces. At the time of that tweet, Sudan was experiencing yet another internet blackout and local calling networks were not functioning, according to several sources.

However, international calls are reportedly still going through. This means that although individuals within Sudan cannot communicate to others within the country by phone, in order to check on a relative inside of Sudan, a source says that Sudanese people can use international callers to make the call to the person they are trying to reach and then wait for the international callers to respond back to them with the information on the loved one.

Because of the internet shutdown, access to official statements on march logistics, demands and objectives of the movement, and general status updates by the majority of Sudanese residents is rare. “I am not getting any direct information from [the Sudenese Professionals Association], Talal Hamadneel”, Algizoly explains,“because we have no access to the internet.“ And Sudan Bukra (Sudan Tomorrow) TV operates on a satellite provider–NileSat–that his family doesn’t use. He is one of the millions of Sudanese citizens who has participated in the protest marches in recent days. The Sudanese Professionals Association is the umbrella organization that serves as the official leadership of the movement and communicates the latest developments to the neighborhood organizing cells. Without internet access, millions of protesters are cut off from direct communication with the heads of the movement.

It is estimated that nearly 4 million people were in the streets in Khartoum on October 30th calling for Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to step down after the prime minister he shared power with–Abdalla Hamdok–was arrested and Burhan claimed control of the government. During the march, three protesters were confirmed killed. In the evening, word came from the SPA of its intent to meet with the various leaders of the movement, including resistance committee heads, to discuss the next steps in the protest.

Many young men returned to their neighborhoods to build and guard barricades at its borders with concrete blocks, burning tires, or other materials that would do the job.

Evident in some social media posts is the fact that in some of these spaces between the barricades and the homes of the community they are protecting, contexts shaped by the music from boom speakers hooked up to mobile phones or people singing and/or playing instruments in that space form around the protest movement. Those music-filled spaces encourage what is happening in Sudan to be viewed through the words describing another revolution from years ago or an imagined space.

Businesses throughout Khartoum and Omdurman are shut down as well, with the exception of small doocans or convenience stores, says Algizoli. “It is not out of fear,” he said, “They chose to do it.”

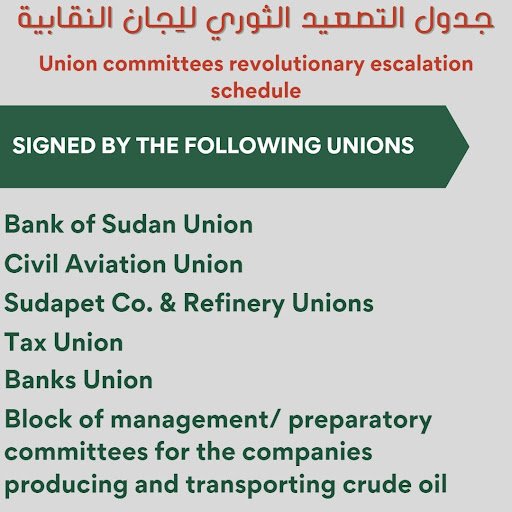

The closed businesses follow calls from the SPA for participation in a large-scale civil disobedience campaign. “Right now,” says El Mardi, “the tactics are not just protests. They include strikes across sectors led by trade unions and a call for civil disobedience, which is very important.” Sudanese workers and industries across Sudan have announced their participation in this campaign. Among those are pilots, doctors, teachers, oil workers, banks, and sugar factory workers.

The coordinated efforts of workers’ organizations in Sudan’s recent protest movement mirror earlier protest movements in Sudan, including its October Revolution of 1964. Gains made towards the objective of establishing a civilian and democratic government in Sudan in 1964 happened in the wake of general strikes, protest marches, and the eventual support of members of the military. This influence of past protest movements is clearly seen in the current movement’s political strategy.

The October Revolution of 1964 in Sudan was a bloodless coup. In the face of growing opposition from a significant segment of the military, the then sitting president, Ibrahim Abbud, stepped down–under pressure, but voluntarily. In the hopes of manifesting another “bloodless” transition to power, the leaders of the recent pro-democracy movement in Sudan have made clear statements urging the participants to maintain a commitment to non-violence. In its October 30th announcement at the tail-end of the massive street march of that day, the Sudenese Professionals Association states, “The masses and the revolutionary forces will not retreat from the peaceful resistance, the occupation of the streets, the general political strike and the mass civil disobedience will continue.”

The adoption of a non-violent strategy has its critics among the Sudanese. One tweeter in the #sudancoup hashtag asks, “But we’re dealing with a very strong & powerful entity in the military & all their armed group supporters - how can we distance them/kick them out of governance without causing more bloodshed? How can we guarantee the safety of this country & its people with these monsters & their guns?”

Muntasir Mohamed, a Sudanese-American computer engineer, on hearing of the recent release from prison of former allies of the deposed former dictator Al-Bashir, expresses discomfort with the idea of moving forward with a completely non-violent approach in light of these developments.

“So now the confrontation between the unarmed Sudanese people vs the army and the militia of the national conference gang ‘Rapid Security Force’...No matter how peaceful we are, the revolution must be protected by an army. The battle has become close between two sides, no room for bargaining, negotiation or half solutions. They should relinquish all power to civilians. Everyone of us believes that. On their side, the treasury of the state and all its weapons and might, have regional and international support from Russia, Israel, Emirates, Egypt, Saudi Arabia. We, the people of Sudan, said our word loud and clear and the whole world heard it, but war is different. It’s not words. Let's be ready for any possibility, to be or not to be.”

El Mardi has heard similar positions expressed by non-Sudanese guests on news shows. Presented as “western experts” on Sudan,” they assert that “it’s unrealistic for the Sudanese people to think that they will win without having military support,” she explains. “That is absurd to me and quite disrespectful because it shows that they don't think that we have the agency and the strength and intelligence to decide how we want to lead our resistance and mobilization.”

Some young people, El Mardi says, have learned a lot about political organizing from the older generation. They “have seen how the older generation organized. We have seen the good sides of it and the stuff that didn't work and are avoiding that. They have also experimented with various tactics and methods throughout the 2018/2019 revolution and still are; and that created a wealth of expertise in mobilization among the young people and the resistance committees.”

After two people were reported shot by troops during Omdurman’s contingent of the March of Millions on October 30th, Algizoly explains that the next move is to go home, assess, and decide what to do next.

Algizoly started out at ten that morning. It is now after two in the afternoon. Yesterday, he said he watched coverage of protests on his family’s television set and was aware of the killing of protesters by military forces. Regardless, he said he still planned to join the protests on the 30th. “We have no other choice,” he said, “We are marching to tell the world how many Sudanese do not want this…This is for all of the world, not just Sudan.” He was joined in the streets that day by mostly young women and men, he says. Their faces filled scores of media reports published about the huge turn-out of the protest.

The statement Algizoly wanted to make was made. He returned home safely, to behind the barricades that his resistance committee members erected.