In a “New” Sudan, the Fight Against the Corona Virus Challenges an Old View of Africa as Passive Victim

Khartoum, Sudan, April 16, 2020

As of the writing of this article, several weeks after it’s first confirmed COVID-19 case in March, Sudan has only 32 confirmed cases of the infection -- according to the World Health Organization website and national reports.

The world reels and moans from the apocalyptic reality of the coronavirus epidemic. But many parts of Africa watch from the outside—as usual. This time, though, being on the margins (in terms of COVID-19 cases) is better than being in the global mainstream as the majority of the world fights the coronavirus.

A former member of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) -- the political arm of a group that waged a struggle with Sudan’s government for more than 20 years--discusses plans for a rooftop disco at the top of Souq Arabie’s Downtown Hotel. At 6pm on a recent evening, Souq Arabie still bustles. Tea ladies’ fires still burn as they prepare hot drinks for their customers as usual. Doocans (small stores) sell as usual.

Seeta chai--a local tea lady’s cafe. (Khartoum, Sudan).

No one is panic buying in huge droves in Sudan because there is no panic. The stores may be closing earlier than usual because of newly instituted curfews, but they will reopen to normal unrestricted business the following day. When the 3 week long full 24 hour lockdown goes into effect on April 18th, small neighborhood stores will be open for a few hours each day to sell their regular stock as well as other necessities that can be found at the large outdoor door markets. Hand sanitizer sits on sale on a shelf by the cash registers at Al Waha's Sena Market—a popular market in central Khartoum—for a 2nd week in a row. The quantity is hardly moving.

Recently, a man selling dollars explains his low rates in Arabic citing coronavirus at some point in his spiel. He gets talked back up, though, when another dealer, communicating via a cell phone, says he will trade the dollars for 6 sdgs more. The sale goes through—112 sudanese pounds to 1 US dollar. There is no real crisis in Sudan, yet. And black dollar market hustling is going on as usual.

However, Sudan—part of a continent with a history of devastating epidemics—is reacting to the growing world crisis with moves that seem to be highly calculated and well-planned. This is the case for other African countries, as well. While pundits are forecasting a delayed doomsday for Africa when the coronavirus increases its presence in African countries with a fury, an argument can be made that several African countries are addressing the problem with well-thought-out and innovative strategies that will keep that from happening.

Sudan's reactions to the crisis reflect a definite concern for the “new” Sudan from government officials trying to protect their thin hold on order and an at-risk economy teetering right on the brink; and ordinary citizens anxious to maintain some degree of normalcy in Sudan as it moves through a temperamental transition period.

Explaining to CNN’s Anderson Cooper in early April why much of the “developing world” may have been spared the brunt of the coronavirus crisis, CNN’s senior medical correspondent, Dr. Elizabeth Cohen, however, offered two possible reasons: people don't travel internationally a lot and testing is not done in large amounts. In other words, the cause has nothing to do with a well-considered strategy that is working, but rather with negligence (not enough testing) or the fact that the citizens of those countries don’t tend to be very internationally mobile, in general.

Cheryl Cohen of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases says in another CNN interview that because of Africa’s lack of “connectedness” to the rest of the world that is heavily affected by the novel coronavirus, the continent’s struggle with it will “lag” behind those other countries. “Africa would be affected after the rest of the world,” she warns.

Graehm Wood makes the same assertion in his article for the Atlantic.(2) “If the spread seems slow to develop, that may be because no African country has the same volume of international travel as the countries elsewhere that are already suffering,” he asserts.

If one looks closely at Khartoum and its surrounding areas over the last few months, one will find a reality that challenges the flat, petrified images of Africa as a weak, passive, and inevitable victim of a devastating coronavirus crisis. In this reality, there are many reasons for the low numbers in Sudan that are related to thoughtful and creative planning. A few are:

1. Early response to the global crisis on a large scale (ie, border and school closings)

2. Creative use of communication systems to inform the public about corona

3. Volunteer efforts by civilians

Sudan’s government ordered all schools closed beginning on March 15. This was after only one confirmed case of COVID-19 had been announced. The next day, all airports, land crossing and ports of entry into Sudan were closed, as well.

Within the same week, the government-funded hotline numbers—221 and 9090 —were publicized, which connected callers to a 24-7 call center where they could pose questions to 100 doctors working in shifts. As well, regardless of whether Sudanese citizens called that number or not for information, whenever a call is placed to anyone in Sudan from a Sudanese number, there is a short message containing information about safety precautions to prevent against the viral infection that is heard before a call is connected.

In addition, there exists a diversity of efforts by individuals not tied to the government that recall the decentralized cooperative operations that played out during the recent revolution of 2018-2019 in Sudan.

In mid-March, a 33-year old owner of a small computer company—who asked to be referred to only as GS—called a friend who volunteers for the Federal Ministry of Health, and asked him “What is the scenario of your call center?”

The call center he was referring to was the one tied to the 221 number. When he learned that there were only 20 phones in the call center, he told his friend, “Really? This is not enough for Sudan. I can help you. My company is a professional team. We can give you any technical support you need for free,” GS explains.

GS and members of his computer software company. (Khartoum, Sudan)

He recalls that about a month ago, a rumor was swirling around Sudan that a baby who had just been born said if people drank tea without sugar at 3 am, they would not get the COVID-19 virus; then right after delivering that statement, the baby died.

Subsequently, the call center was inundated with more than 4000 calls in one day from people asking the doctors on duty whether the rumor was true. GS proposed using an app with a chat feature instead of the call center so that the government can better deal with high volumes of questions and requests for information from the public.

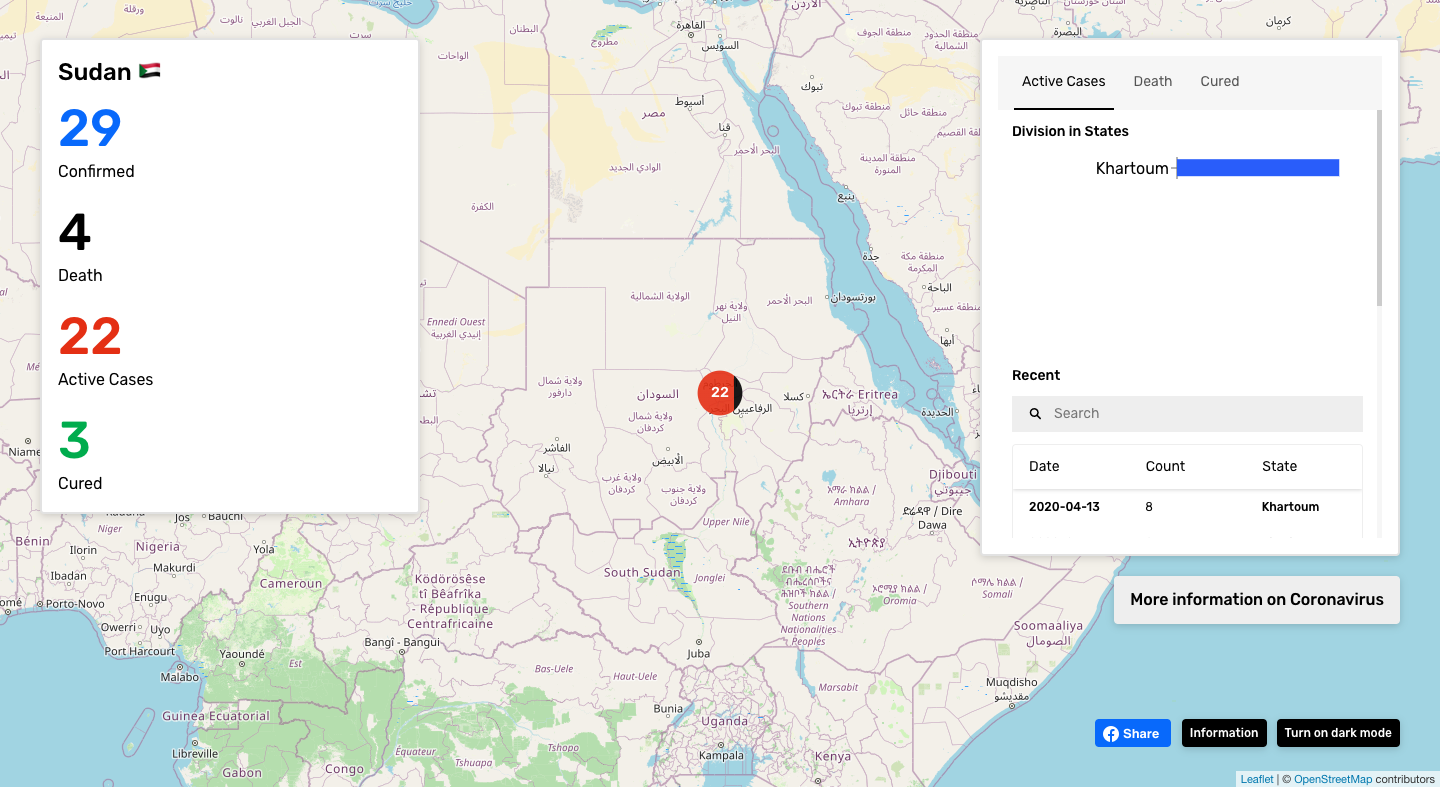

GS and his team went to work on the app, and two weeks later had a prototype. It offers a chat feature; a tracker, showing the location and number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, deaths, and recoveries; and 6 other features that, because of their sensitive national security nature, he did not want to disclose. In addition, if the government agrees, information can be pulled directly from immigration databases in Sudan to address the issue of inaccurate tracking information (ie, phone numbers and addresses) provided after travellers have already passed through main points of entry.

Coronavirus Tracking Map--one of the features of the app that GS’s company developed.

GS requested an audience with the Khartoum Ministry of Health to present the app. It was granted, and his app was awarded a certificate of approval for its technical qualities from the agency. He then recently met with Dr. Akram of the Federal Ministry of Health. He is waiting for feedback from that meeting.

At the grassroots level, neighborhood organizers reached out to doctors for directions on making antiseptics, and then made solutions of it themselves and distributed bottles of the sanitizers free-of-charge to residents.

Akram (in yellow shirt on left) and members of the resistance committee preparing sanitizing solutions in a local school in the neighborhom of Algihab. (Omdurman, Sudan).

A batch of sanitizing solution prepared by the Alfgihab Resistance Committee for distribution to residents of their neighborhood at no charge. (Omdurman, Sudan.)

As well, groups within neighborhoods organized the delivery to its residents of an important staple of Sudan—bread. Resistance committees that worked at the grassroots level during the recent revolution are directing these efforts. Everyday at 11 pm members of a resistance committee in the neighborhood of Alfgihab in Omdurman—a sister city to Khartoum—meet to begin the work of picking up 6000 pieces of bread from a local bakery, counting each piece, and then selling the bread to the neighborhood residents at two distribution sites, according to Akram Madny, a 19-year old resistance committee member.

Members of the Alfgihab Resistance Committee protecting bread supplies during the process of its delivery to distribution points in the Alfgihab neighborhood. (Omdurman, Sudan.)

This was work that was begun before the coronavirus pandemic as an effort to support communities during a volatile time when the country witnessed political upheaval related, in part, to shortages or price hikes of important commodities like bread. The committees' role as grassroots coordinators and rank-and-file members of the 2018-2019 revolution in Sudan changed to the “protector[s] of the revolution,”—as Akram calls it—in the wake of the historic political upheaval, bringing important social services to neighborhoods, as the new government reshapes itself after 30 years of ex-President Omar Bashir's rule.

Another grassroots initiative is the Moves Charity Group. It began in 2014 as a group of women who funded charity projects with 10% of the proceeds from their sale of make-up. Its influence in Sudan’s charity landscape has grown since then. During the 2018-2019 revolution, the group provided more than 10,000 bottles of water and more than 5000 meals to protestors; as well as more than 2000 pieces of clothing to homeless children, explains Alaa Salih Hamadto, the organization’s facebook group administrator. Recently, after conversations with Sudan’s Federal Ministry of Health about the country’s current equipment needs in the face of the anticipated battle with COVID-19, MOVES was able to raise 7 million sudanese pounds (about 50,000 US dollars) to purchase 71 ventilators. 22 ventilators are going to Omdurman Hospital, another 22 to Alshab Hospital in Khartoum, and at least 17 will go to others areas outside of Khartoum, Hamadto says.

Donations from the MOVES charity group of ventilators to support Sudan’s fight against COVID-19. (Khartoum, Sudan)

Alaa Salih Hamadto (right) posing with another MOVES member and a truckload of ventilators funded by donations to MOVES. (Khartoum, Sudan)

These are deliberate efforts being taken in Sudan to build up the defenses of the Sudanese people and keep COVID-19 cases low. It might be the case that Sudan is not testing enough or is just lucky. Or Sudan’s numbers may be low because of another possibility: it is doing a lot of things right on purpose.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Vania Gulston is a freelance writer, radio journalist, and founder of WJYN Radio, a community radio station in Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in the New African Magazine, The New Amsterdam News, TAP Magazine, and Law at the Margins, among others. She studied history and folklore, and then later earned her masters in social studies education. She splits her time between Khartoum, Philadelphia, and New York City.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LINKS:

1. David Mackenzie. “Experts: Coronavirus Could Hit African Countries Hardest.” CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/16/africa/africa-coronavirus-travel-restrictions-foreigners/index.html)

2. Graeme Wood. “Think 168,000 Ventilators Is Too Few? Try Three.” The Atlantic. April 10, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/why-covid-might-hit-african-nations-hardest/609760/

3. GS’s Coronavirus Tracking Map for Sudan: https://dev.secrule.io/maps/covid-19/?fbclid=IwAR2wN72IiygvI4-pjE_86BcDkkMEIbNwt5uAi1Y_CdblAeHWetOXdQ_cJVA

4. MOVES Charity Group’s @ https://www.facebook.com/MOVES-Charity-1580162662246404/

An example of an organization that is driven by the importance of Art in Africa is The Muse Creative Studios in Khartoum, Sudan. We had the privilege of speaking to them to learn more about Art in Sudan, and what they are doing to make a difference.

The Muse is a creative enterprise that aims to promote art in Sudan. Founded in 2019 by Reem Al Jeally, it was built off the lack of support and representation of Artists in Sudan. Despite there being a cornucopia of talented artists in Sudan, they often remain in the shadows. Without proper support, a thriving community of creatives remains dormant. An unfortunate reality that many African countries can relate to. One that is, however, slowly changing.